In December 2023, China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a regulatory notice banning the export of gallium and germanium without a government licence. There was no emergency summit. No hashtag trended. Most Western policymakers had never heard of either element, which is itself the point. Gallium is essential for semiconductor chips, LEDs, and 5G infrastructure. Germanium is critical for fibre optics, infrared lenses, and satellite systems. China controlled roughly eighty per cent of global gallium production and sixty per cent of germanium. With a single bureaucratic notice, Beijing demonstrated that it could switch off a supply chain underpinning the digital economy of every Western nation — and that nobody in Washington, London, or Brussels had thought to prepare a contingency plan.

The geopolitical history of the modern world can be told through whoever controls the critical resource of the age. The British Empire ran on coal — the fuel that powered its navy, its factories, and its railways across a quarter of the globe. The American century ran on oil — the resource whose control shaped the Middle East, justified coups, and funded the military-industrial complex. The next century will run on a basket of minerals that most people cannot name, mined in places most people cannot find on a map, and processed overwhelmingly in a single country. The Ottoman Empire ran a multinational state for six centuries on geography and administrative talent, which is five centuries longer than the West has managed to maintain its supply chain independence. If the pattern holds, the nations that control the extraction, processing, and refining of lithium, cobalt, rare earths, copper, nickel, and graphite will shape the twenty-first century the way coal shaped the nineteenth and oil shaped the twentieth. Those that do not will discover what it feels like to be on the wrong end of an oil embargo — except this time the embargo covers everything.

The Colonial Resource Playbook

The scramble for critical minerals is not new. What is new is the identity of the scrambler.

When King Leopold II of Belgium acquired the Congo basin in 1885, he did so because the territory contained rubber, ivory, and minerals. Rubber was the critical resource of the late nineteenth century — essential for the tyres, hoses, and gaskets that made the industrial age function. Leopold’s regime extracted it through a system of forced labour so brutal that it killed an estimated ten million Congolese. The hands of those who failed to meet quotas were severed. Profits were immense. This was resource extraction in its most naked form — no euphemism, no supply chain jargon, just coercion and death in the service of an industrial economy that could not function without the material.

Britain operated a rather more genteel version in Malaya. Tin was the strategic mineral of the early twentieth century — essential for canning, soldering, and industrial alloys — and by 1940, Malaya supplied roughly a third of the world’s tin. When Japan seized the Malay Peninsula in 1942, the Allies faced an immediate shortage. Rubber followed the same pattern: Japan’s capture of Southeast Asian plantations forced the United States into a crash programme to develop synthetic rubber — one of the war’s most consequential industrial achievements.

Oil was the colonial resource at its grandest scale. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company — later BP — was established in 1909. The British government took a controlling stake in 1914 at Winston Churchill’s insistence, because the Royal Navy’s shift from coal to oil had made Persian crude a matter of national survival. For the next half century, the “Seven Sisters” — seven Western oil companies — controlled the majority of global oil production, refining, and distribution. When Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, attempted to nationalise Anglo-Iranian Oil in 1953, Britain and America organised a coup to remove him. The message was unsubtle: the resource belonged to whoever had the power to hold it.

What made the Seven Sisters effective was not merely their control of the wellhead. It was their control of the entire value chain — from the hole in the ground to the petrol station on the corner. A country could nationalise its wells, but without refineries, tanker fleets, and distribution networks, it sold crude at a discount to the very companies it had expelled. That pattern — control of processing, not mining — is precisely what China has replicated with critical minerals. And it is worth remembering, because the playbook is the same. Only the players have changed.

The Periodic Table of Power

The energy transition — electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, grid-scale batteries, advanced semiconductors — depends on a set of minerals that barely featured in geopolitical discourse a decade ago.

Lithium is the foundation of rechargeable batteries. Australia mines roughly forty-seven per cent of the world’s lithium; Chile and Argentina hold vast reserves in brine deposits. But mining is only the first step. China processes approximately sixty-five per cent of the world’s lithium into battery-grade material. Australia digs it out of the ground. China turns it into something useful. The West buys the finished product.

Projected Critical Mineral Demand Growth (2023–2040)

The energy transition requires a mining revolution of unprecedented scale

Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2024; BloombergNEF

Cobalt tells a starker story. Roughly seventy-three per cent of the world’s cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, much of it through artisanal operations involving hand-digging, minimal safety equipment, and, in some operations, child labour. Chinese firms own or hold significant stakes in many of the largest Congolese mines. The cobalt is shipped to China for refining. The West has almost no domestic cobalt processing capacity.

Rare earth elements — neodymium, dysprosium, praseodymium, and their relatives — are essential for the permanent magnets in wind turbine generators, electric vehicle motors, and guided weapons systems. China mines approximately seventy per cent of the world’s rare earths and processes closer to ninety-eight per cent. In 2010, during a maritime dispute with Japan, China briefly restricted rare earth exports. Prices spiked several hundred per cent overnight. Japan, which depends on rare earths for its electronics and automotive industries, scrambled to diversify. Fifteen years later, China’s processing monopoly remains largely intact.

Where the Minerals Are: Major Mining and Processing Nations (2024)

Minerals are mined in the Global South and processed in China — a supply chain geography that mirrors colonial extraction

Source: USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024; IEA

Copper is the silent crisis. Every electric vehicle uses roughly three to four times more copper than an internal combustion engine. Every wind turbine uses tonnes of it. Every kilometre of upgraded electrical grid uses more still. Demand is forecast to double by 2035 as electrification accelerates, yet Chile and Peru — which account for roughly thirty-eight per cent of mine production — face declining ore grades, water scarcity, and mounting community opposition to new mines. No major new copper deposit has been discovered in over a decade. The copper shortage may prove more consequential than any other bottleneck, because copper is the one mineral for which there is no ready substitute in electrical applications.

Nickel is dominated by Indonesia, which produces roughly half the world’s supply, much of it through processing operations financed by Chinese investment. The environmental cost has been severe — nickel smelting in Sulawesi has devastated local forests and waterways — but the output has been immense.

China's Share of Global Mineral Processing (2024)

Even minerals mined elsewhere are shipped to China for processing — a chokepoint with no equivalent in history

Source: IEA Critical Minerals Report 2024; USGS

Graphite — essential for every lithium-ion battery anode — is sourced predominantly from China, which mines sixty-five per cent of natural graphite and produces virtually all of the world’s synthetic graphite.

The picture is not a single bottleneck. It is an entire supply chain that, at its most critical processing stage, routes through one country. The West’s energy transition is, in its current form, a Chinese supply chain with Western branding.

China’s Monopoly — Built, Not Given

China’s dominance of critical mineral processing is not an accident of geology. It is the result of three decades of deliberate, patient industrial strategy.

Beginning in the 1990s, while Western economists were celebrating the end of history and the triumph of free markets, China invested systematically in mineral processing capacity. The strategy was elegant in its simplicity: let other countries bear the environmental costs and political risks of mining, then capture the far more valuable refining and chemical processing stages with state-subsidised capacity that undercut Western competitors on price. One by one, processing plants in the United States, Europe, and Japan found they could not compete. They closed. China absorbed their market share. The same playbook had worked in solar panels — Chinese state subsidies flooded the global market with cheap photovoltaic panels, drove European manufacturers into bankruptcy, and by 2020 China controlled over eighty per cent of global solar manufacturing.

The Belt and Road Initiative extended the strategy upstream. Minerals-for-infrastructure deals in the DRC secured cobalt. Nickel smelting investments in Indonesia secured that supply. Stakes in Chilean and Argentine lithium operations secured battery feedstock. Deng Xiaoping reportedly remarked in 1992 that “the Middle East has oil; China has rare earths.” Three decades later, China has effective control over the processing of lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and rare earths as well.

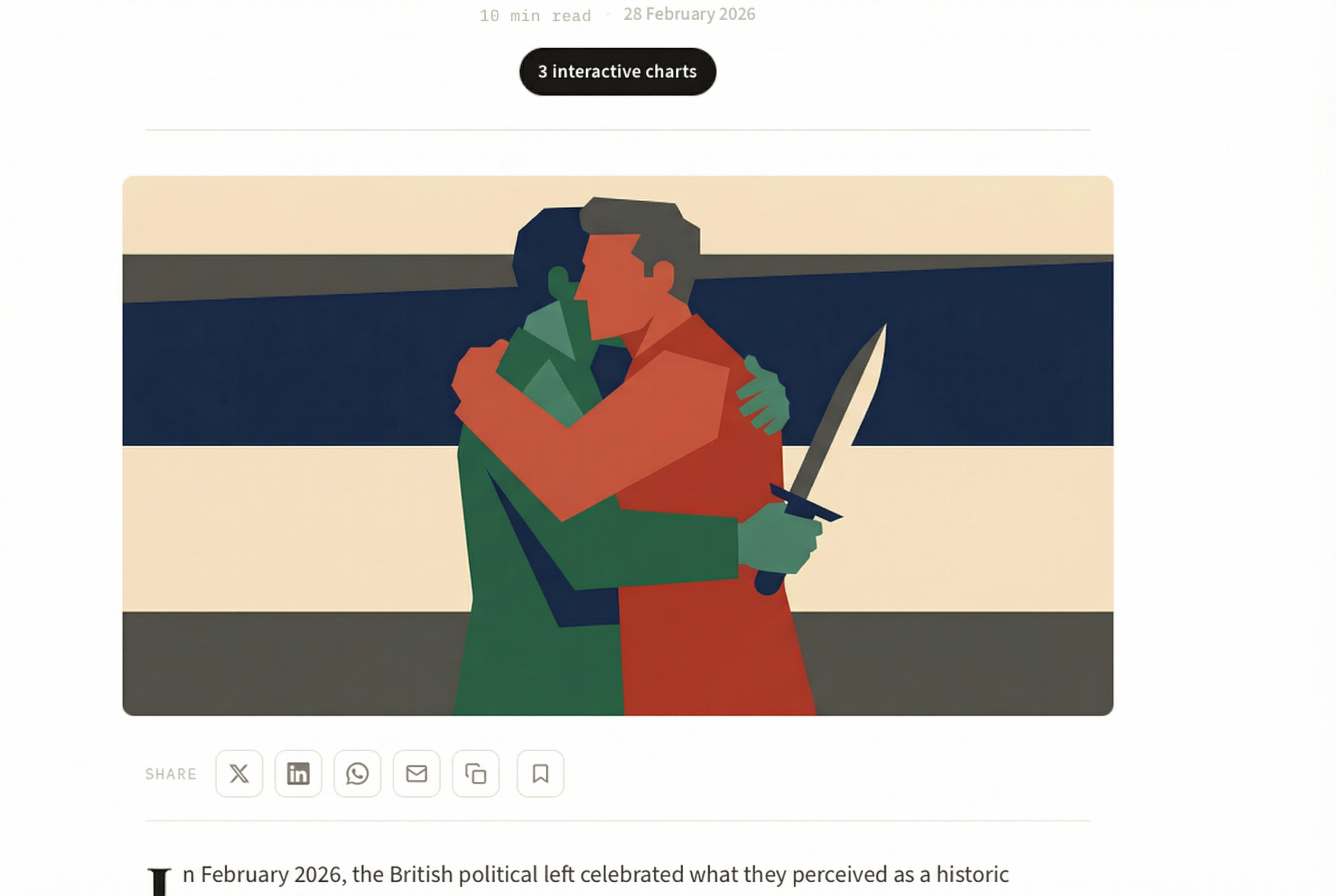

The West’s critical mineral supply chain now runs through China the way Europe’s gas supply ran through Russia — and February 2022 demonstrated, with terrible clarity, how quickly that kind of dependency can be weaponised.

The Western Response — Too Little, Too Late?

The European Union passed the Critical Raw Materials Act in 2023, setting targets for 2030: mine ten per cent of strategic mineral needs domestically, process forty per cent, recycle twenty-five per cent, and cap dependency on any single third country at sixty-five per cent. But supply chain security is fundamentally a national responsibility — and the states that have acted decisively on resource strategy, from France’s nuclear programme in the 1970s to China’s mineral processing build-out, did so through national decision-making, not through supranational consensus. The EU’s slow, harmonised approach is itself part of the problem: permitting a new mine in Europe takes an average of twelve to sixteen years, a timeline partly dictated by EU-level regulatory layers that no single member state can bypass. China can build a processing plant in eighteen months. The asymmetry is not merely logistical. It is structural: when twenty-seven nations must agree before a refinery can be built, the nation that needs no one’s permission will win.

The United States Inflation Reduction Act committed over 369 billion dollars in clean energy incentives and triggered significant investment in domestic battery manufacturing. But the upstream supply chain — the mines, the refineries, the chemical processing — remains overwhelmingly Chinese. Building a lithium refinery or rare earth separation plant takes years, costs billions, and requires specialised chemical engineering talent that the West has largely allowed to atrophy. The last American rare earth separation facility closed in the early 2000s. Rebuilding that capability is not merely a matter of money; it requires training a generation of engineers in metallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes that Western universities stopped teaching because there was no domestic industry to employ the graduates.

The historical parallel that should concentrate minds is the Allied resource mobilisation of the Second World War. When Japan captured Southeast Asia’s rubber plantations, the United States launched a crash programme to develop synthetic rubber at industrial scale — and succeeded within two years. The Manhattan Project built an atomic weapon in three. The Liberty Ship programme produced vessels at a rate of one every forty-two days at peak. These achievements demonstrated that a concentrated national effort can accomplish what peacetime incentive structures cannot. But they worked because the political will matched the perceived threat. Bombs were falling. The dependency was not abstract.

No bombs are falling over critical minerals. The dependency is abstract and diffuse, the threat scenario is hypothetical, and the response has been legislative and incremental rather than strategic and urgent. For thirty years, Western orthodoxy held that free trade and globalised supply chains were inherently efficient and that government-directed industrial policy was a market distortion. That was a convenient belief when Western companies benefited from open markets. It is rather less convenient now that those open markets have delivered a Chinese monopoly on the processing of virtually every mineral required for the energy transition and modern defence.

What Comes Next

The twenty-first century will be defined by a basket of minerals whose combined availability determines whether a nation can build electric vehicles, deploy renewable energy, manufacture semiconductors, and field a modern military. The nations that control these supply chains will occupy the strategic position that coal gave Britain in the nineteenth century and oil gave the United States in the twentieth.

China understood this thirty years ago — perhaps because its own history of foreign resource exploitation gave its strategists a clearer view of what resource dependency means than the West’s comfortable post-war abundance ever could. It invested when the minerals were obscure, secured mining rights across three continents, built processing capacity that the West dismissed as uneconomical, and trained the engineers and chemists that Western universities stopped producing. The West’s window to respond is narrowing but has not yet closed. The British Empire learned what happens when you depend on a single source for a critical commodity — its dependence on American cotton during the Civil War nearly strangled the Lancashire mills. The United States learned with Middle Eastern oil in 1973. Europe learned with Russian gas in 2022. The lesson is always the same, and it is always learned too late.

The question is not whether China’s critical mineral supply chain will be weaponised further. It already has been — the gallium and germanium restrictions were not a warning shot but a demonstration. The question is whether the West will build the domestic capacity to withstand it, or whether critical minerals will join the long and melancholy list of strategic dependencies that were recognised too late and paid for too dearly. Send that to anyone who still thinks the energy transition is just a matter of wind turbines and political will.