On 7 October 2022, the United States Bureau of Industry and Security issued a set of export controls that amounted to an act of economic warfare. The regulations did not merely restrict the sale of advanced semiconductors to China. They banned American citizens and permanent residents from working for Chinese chip companies. They prohibited the export of semiconductor manufacturing equipment capable of producing chips below 14 nanometres. They cut off China’s access to the tools, the talent, and the technology required to build the most advanced computing hardware on Earth. The scope was breathtaking. In a single regulatory action, the United States had attempted to freeze the technological development of a civilisation of 1.4 billion people. Jake Sullivan, the US National Security Advisor, described the objective with unusual candour: the goal was not merely to maintain America’s technological lead, but to widen it, to ensure that China could not close the gap (Miller, 2022).

The target of these restrictions was, in the first instance, a single factory complex: the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s fabrication plants in Hsinchu, southern Taiwan. TSMC manufactures roughly 90 per cent of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, the chips that power artificial intelligence, advanced weapons systems, autonomous vehicles, and virtually every piece of critical digital infrastructure in the modern world (Semiconductor Industry Association, 2024). A single company, on an island of 23 million people situated 130 kilometres from a nuclear-armed superpower that claims it as sovereign territory, produces the component without which neither the American nor the Chinese economy can function. This is not a supply chain. It is a single point of catastrophic failure.

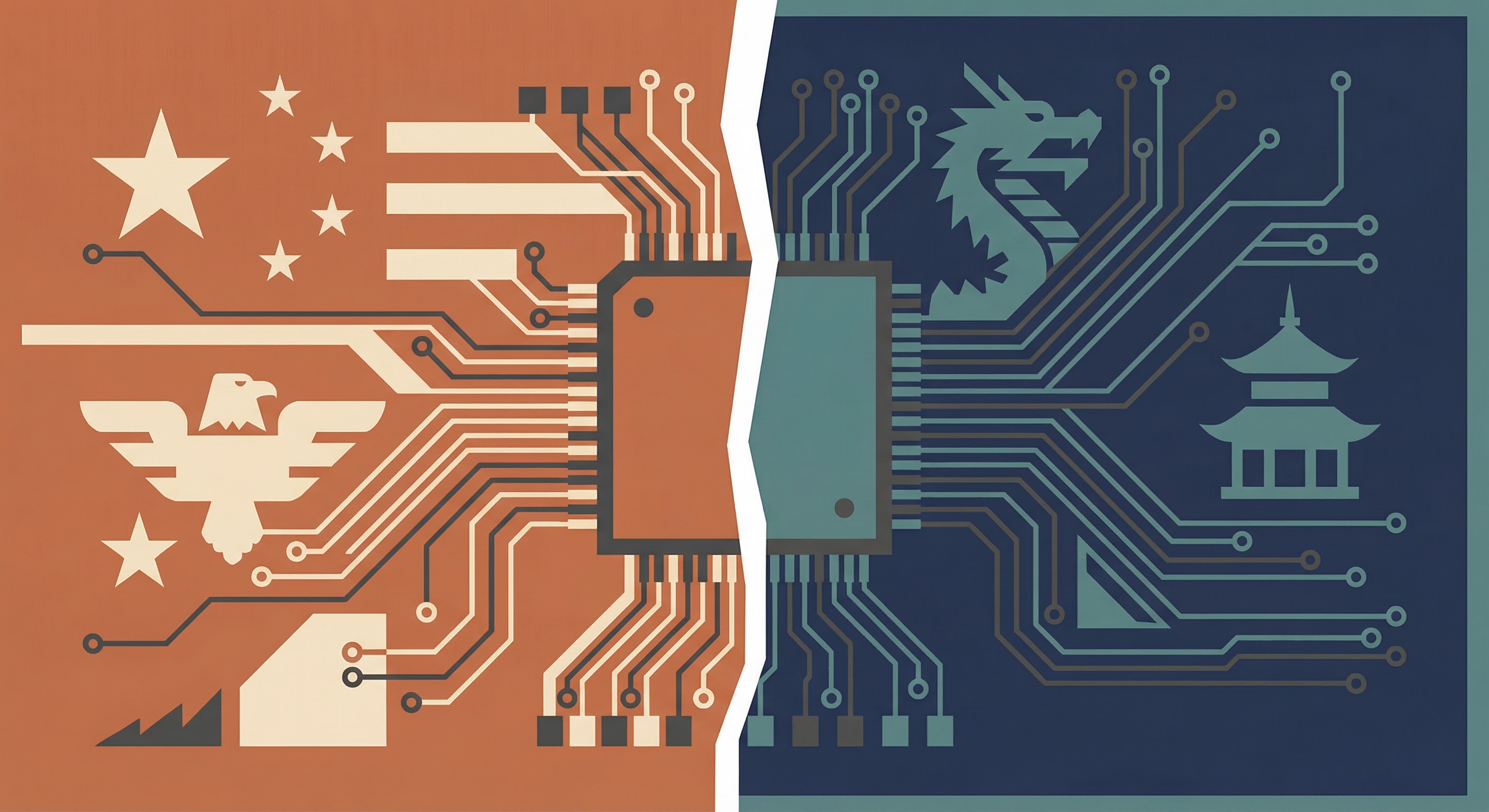

The Cold War divided the world into two blocs with different economic systems. The tech war is dividing it into two blocs with different search engines. The stakes, improbably, may be higher. An economic system can be reformed, as Russia demonstrated, painfully, in the 1990s. A technological ecosystem, once it has been built, standardised, and embedded into the infrastructure of a civilisation, is vastly more difficult to change. The world is not merely splitting into two spheres of political influence. It is splitting into two incompatible technological civilisations, and every nation on Earth will, within the next decade, be forced to choose which one to join.

The Chokepoint: Why Semiconductors Matter More Than Oil

The twentieth century was shaped by control of hydrocarbons. The twenty-first will be shaped by control of semiconductors. This is not a metaphor. It is an observation about which physical resource determines the balance of global power.

Oil mattered because it was the primary energy source for industrial economies and the fuel for modern warfare. Nations that controlled oil, or the sea lanes through which it flowed, held decisive strategic advantage. The United States’ rise as a global power was inseparable from its domestic oil production. Britain’s shift from coal to oil-powered warships before the First World War, at the instigation of Winston Churchill, made the Middle East a permanent theatre of great-power competition. The OPEC embargo of 1973 demonstrated that a cartel controlling a critical commodity could hold the industrialised world to ransom.

Global Semiconductor Market Share by Region (2024)

A handful of chokepoints control the world's most critical technology

Source: SIA; Gartner; ASML Annual Report 2024

Semiconductors occupy an analogous position, but with a critical difference: the supply chain is far more concentrated. Oil is produced by dozens of countries across every continent. Advanced semiconductors, those at the 7-nanometre node and below, are produced by exactly three companies: TSMC in Taiwan, Samsung in South Korea, and Intel in the United States. The machinery required to manufacture these chips is produced by a single company: ASML, based in Veldhoven, the Netherlands, which holds a complete monopoly on extreme ultraviolet lithography machines. There is no second source. There is no alternative. Every advanced chip in every advanced device on Earth passes through a supply chain that could fit inside a single mid-sized European town (Miller, 2022).

Chris Miller, in his definitive account of the semiconductor industry, describes this concentration as an accident of economics rather than a conspiracy of geopolitics. The cost of building a cutting-edge fabrication plant now exceeds $20 billion. The technical expertise required to operate it takes decades to develop. The network of suppliers, chemical companies, gas producers, and equipment manufacturers that support it is global, intricate, and irreplaceable. No country, not even the United States or China, can replicate this ecosystem from scratch. Both are trying. Neither has yet succeeded (Miller, 2022).

The historical parallel is instructive. During the Second World War, the Swedish ball-bearing manufacturer SKF supplied bearings to both the Allies and the Axis. Ball bearings were essential to virtually every piece of military equipment: aircraft engines, tanks, submarines, artillery. Albert Speer, Hitler’s armaments minister, told his interrogators after the war that a sustained Allied bombing campaign against the Schweinfurt ball-bearing plants might have ended the war far sooner than it did. The Allies understood this: the raids on Schweinfurt in 1943 were among the costliest air operations of the war, with the US Eighth Air Force losing 77 bombers in two missions. The lesson was clear. Whoever controls the chokepoint controls the war (Speer, 1970).

The United States has understood this lesson and is acting on it. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 committed $52 billion to domestic semiconductor manufacturing and research. TSMC is building fabrication plants in Arizona. Intel is expanding in Ohio. Samsung is building in Texas. The objective is not merely economic competitiveness but strategic redundancy, to ensure that if Taiwan is blockaded, invaded, or otherwise rendered inaccessible, the United States can still produce the chips it needs.

China has understood the same lesson. Since 2014, Beijing has poured over $150 billion into its domestic semiconductor industry through a succession of national funds (Rhodium Group, 2024). Huawei’s Kirin 9000S chip, manufactured by China’s SMIC using a 7-nanometre process that Western analysts had believed was beyond China’s current capability, demonstrated in 2023 that export controls had slowed but not stopped Chinese progress. The chip was inferior to its TSMC-manufactured equivalents. It was also proof that China would build its own stack, whatever the cost.

Historical Precedents for Technology Bifurcation

The splitting of a single technological civilisation into two parallel and incompatible systems has happened before. The consequences have, without exception, been profound, and have always ended with one system’s collapse.

The most ancient example is the division between Rome and Persia. For seven centuries, the Roman and Sasanian Persian empires existed as rival civilisations occupying the western and eastern halves of the known world. Each developed its own engineering traditions, its own military technology, its own administrative systems. Roman concrete, aqueducts, and road-building techniques had no equivalent in the Persian world. Persian irrigation systems, cavalry tactics, and postal networks had no equivalent in the Roman world. Trade existed between them, but technology transfer was minimal and frequently treated as espionage. The two empires fought thirteen major wars between 54 BC and 628 AD, an average of one every fifty-two years, and the technological divergence between them was both a cause and a consequence of permanent hostility (Dignas and Winter, 2007).

What ultimately destroyed both was not each other but the exhaustion that their rivalry produced. By the time the Arab armies emerged from the peninsula in the 630s, Rome and Persia had spent themselves in a final catastrophic war from 602 to 628. The parallel systems that each had built, military, administrative, economic, proved too rigid to adapt. Neither could borrow from the other quickly enough to respond to a threat that neither had anticipated. The Arabs, meanwhile, had absorbed military techniques from both sides without being locked into either system, and they used that flexibility to devastating effect. Within two decades, they had conquered the entirety of the Persian Empire and stripped Rome of its wealthiest provinces: Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. Parallel systems create parallel vulnerabilities, and a sufficiently agile third party can exploit both simultaneously.

The Cold War provides the modern precedent. The Soviet Union built an entire technological civilisation from scratch: separate computing architectures, separate aerospace programmes, separate telecommunications networks, separate industrial standards. Soviet engineers were often brilliant. The Soyuz rocket, designed in the 1960s, still flies today. The MiG-25 Foxbat so alarmed Western intelligence that its defection to Japan in 1976 prompted a complete reassessment of Soviet capabilities.

But the separated system fell behind. Without access to the competitive pressures and collaborative innovation networks of the Western technology ecosystem, Soviet technology became progressively less capable relative to its Western counterparts. The ES EVM mainframe series, a clone of IBM’s System/360, was obsolete before it entered production. The Soviet semiconductor industry never advanced beyond the equivalent of early 1980s Western capability. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev took power in 1985, the technology gap had become an unbridgeable chasm. The Soviet economy could not produce the computers, the communications equipment, or the precision-guided weapons that defined the new era of military and economic power. The system did not reform. It collapsed (Kotkin, 2001).

There is a subtler precedent still. The Protestant-Catholic intellectual schism of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries created two parallel knowledge ecosystems within Europe itself. Protestant nations, the Netherlands, England, parts of Germany, Scandinavia, developed traditions of empirical enquiry, open publication, and collaborative scientific exchange that accelerated the Scientific Revolution. Catholic nations, Spain, Portugal, much of Italy and France, maintained systems of intellectual control through the Inquisition and the Index of Forbidden Books that suppressed or delayed the adoption of new ideas. Galileo was silenced. Copernicus’s work was banned. The result was not the destruction of Catholic civilisation, but a decisive shift in the balance of power. Spain, which had been the richest and most powerful nation in Europe in 1500, was a declining backwater by 1700. The Dutch Republic, a tiny collection of swamp provinces with a fraction of Spain’s population, became the wealthiest society in Europe, largely because it was the most intellectually open. The Royal Society in London, founded in 1660, became the prototype for collaborative scientific institutions that drove innovation across the Protestant world. By 1700, the centre of European innovation had moved irreversibly from the Mediterranean to the North Sea. The nations that controlled the flow of information controlled the future (Mokyr, 2002).

The relevance to the current bifurcation is direct. China’s Great Firewall is the modern equivalent of the Index of Forbidden Books: a systematic effort to control which information its citizens can access, which ideas they can encounter, which foreign innovations they can adopt. It works, up to a point. It maintains social stability and prevents the kind of information chaos that democratic societies struggle with. But the historical record suggests that information control, however effective in the short term, imposes a cumulative innovation tax that compounds over decades. The question is whether China’s sheer scale and engineering talent can overcome that tax. The Catholic Church had plenty of brilliant minds. It was not a shortage of intelligence that held back Catholic Europe. It was the system within which that intelligence operated.

The Bifurcation: US-Aligned vs. China-Aligned Technology Stacks

Two parallel technology ecosystems are emerging across every layer of the stack

Source: Rhodium Group; Eurasia Group; author analysis

The pattern is consistent. When a single technological civilisation splits into two parallel systems, both sides pay an enormous cost. But the system that is more open, more competitive, and more tolerant of disruptive innovation wins in the long run. The closed system may move faster initially, central planning can concentrate resources with impressive speed, but it cannot sustain the pace of innovation that emerges from decentralised competition.

The Bifurcation Map: Two Stacks, Two Worlds

The technology bifurcation between the United States and China is no longer theoretical. It is visible, measurable, and accelerating across every major technology category.

The Tech Bloc Map: US-Aligned, China-Aligned, and Non-Aligned (2025)

Every nation is being pulled towards one tech ecosystem — some are trying to straddle both

Source: Author analysis based on 5G deployment, AI partnerships, and payment system adoption

In artificial intelligence, the split is now functionally complete. The Western world runs on OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, Anthropic’s Claude, and Meta’s Llama. China runs on Baidu’s Ernie, Alibaba’s Qwen, and, most impressively, DeepSeek, the open-source model that stunned Western observers in January 2025 by matching frontier American models at a fraction of the reported training cost. DeepSeek’s R1 model demonstrated reasoning capabilities comparable to OpenAI’s o1 while being open-weight and trainable on less advanced hardware. The two AI ecosystems are developing in parallel, each optimised for its own language, its own data environment, and its own regulatory framework. They are not interoperable. A model trained on Chinese internet data does not understand the Western internet, and vice versa (Rhodium Group, 2024).

In social media, the bifurcation is older and more entrenched. The Western stack, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, X, has no presence in China. The Chinese stack, WeChat, Weibo, Douyin, Xiaohongshu, has no presence in the West, with the notable and contested exception of TikTok’s international version, which the United States has spent three years attempting to ban or force into American ownership. The average Chinese citizen and the average American citizen inhabit entirely separate information environments. They read different news, watch different videos, consume different narratives, and hold different assumptions about the world, not because of individual choice, but because of infrastructure. Two generations ago, during the Cold War, citizens on either side of the Iron Curtain at least knew that the other side existed and had some rough idea of how it worked. Today’s information bifurcation is more complete than anything the Soviets achieved, because it is built into the architecture of the internet itself rather than imposed by border guards and jamming stations.

In financial technology, two parallel payment systems now operate globally. The Western system, Visa, Mastercard, SWIFT, remains dominant in Europe, the Americas, and much of Asia. But China has built UnionPay, which now has more cards in circulation than Visa and Mastercard combined at roughly 7 billion, along with Alipay and WeChat Pay, which between them process more mobile transactions annually than every Western payment platform combined. Russia, after its exclusion from SWIFT in 2022, pivoted rapidly to Chinese payment infrastructure. Iran and North Korea already operate outside the Western financial system entirely. The question for every other country is not whether these two systems will coexist but which one will handle their transactions.

In telecommunications, the bifurcation centres on 5G infrastructure. The Western stack, Ericsson and Nokia, competes against Huawei for the right to build the mobile networks on which every other technology depends. The United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and most of the EU have banned or restricted Huawei equipment. But much of Africa, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America has chosen Huawei, because it is cheaper, often better, and comes with Chinese government financing that Western companies cannot match.

In space, Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation is providing broadband internet access across the Western-aligned world. China is building its own equivalent, the Guowang constellation, planned to comprise 13,000 satellites. Russia is excluded from Starlink. Ukraine depends on it. The satellite internet layer, which may ultimately replace terrestrial networks for large parts of the developing world, will be bifurcated from birth.

In operating systems, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android dominate the Western world. Huawei’s HarmonyOS, forced into existence by the American ban on Huawei’s access to Google services, now runs on over 100 million devices in China and is expanding into markets where Huawei has a strong presence. An operating system is not merely software. It is the gateway through which a user accesses every service, every application, and every piece of information. The choice of operating system is, in practice, the choice of technological civilisation.

The countries that have chosen are broadly predictable. The Five Eyes nations, the EU, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are firmly in the American stack. China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea are in the Chinese stack. The interesting, and consequential, middle ground is occupied by the nations that have not yet chosen, or are attempting to straddle both: India, the Gulf states, most of Southeast Asia, most of Africa, Brazil, and Indonesia. These nations are running Western social media alongside Chinese 5G, processing payments through both Visa and UnionPay, and training AI models on infrastructure purchased from both sides. This ambiguity cannot last. As the two stacks diverge technically, as standards become incompatible, as data cannot flow between ecosystems, as security requirements force binary choices, the non-aligned middle will narrow and eventually disappear.

Who Wins? The Open System and Its Enemies

History offers a reasonably clear answer to the question of which technological civilisation will prevail, and it is not the answer that either Washington or Beijing would find entirely comfortable.

The open system wins. It wins reliably, consistently, and over the long run. Athens defeated Sparta’s closed militaristic society, not on the battlefield, where Sparta prevailed, but in the contest of ideas, culture, and economic dynamism that outlasted both city-states. The Roman Republic, with its messy political competition and absorption of foreign talent, conquered the more disciplined but less adaptive Hellenistic kingdoms. The Protestant North overtook the Catholic South. The liberal democracies of the West buried the command economies of the Soviet bloc. In every case, the system that permitted more internal competition, more individual initiative, and more tolerance of failure produced more innovation and more wealth than the system that attempted to direct these things from the centre (Allison, 2017).

China’s centrally directed technology ecosystem has produced remarkable results in remarkably little time. Its high-speed rail network, its 5G rollout, its electric vehicle industry, its solar panel manufacturing dominance, and, most recently, its AI capabilities have demonstrated that a state-directed system can move with extraordinary speed when it identifies a clear target. DeepSeek’s achievement, building a frontier AI model despite having restricted access to the most advanced American chips, is a genuine engineering triumph. The controlled system excels at mobilisation.

But mobilisation is not innovation. The Soviet Union mobilised brilliantly. It built nuclear weapons within four years of the Americans, launched the first satellite, put the first human in space, and built the world’s largest submarine fleet. It did all of this through centralised direction, massive resource allocation, and the ruthless suppression of competing priorities. And then it stopped. It stopped because centralised systems are superb at catching up to a defined frontier but incapable of pushing beyond it. Pushing beyond the frontier requires the kind of chaotic, wasteful, unpredictable experimentation that centralised systems cannot tolerate, because most experiments fail, and failure in a centralised system is someone’s fault (Kotkin, 2001).

The United States’ greatest risk is not that China will out-innovate it. The historical pattern suggests that is unlikely, so long as the American system remains open. The risk is that Washington will overplay its hand and, through excessive controls, push China to achieve the self-sufficiency that it would otherwise never have attained.

There is a precise historical parallel. In 1806, Napoleon imposed the Continental System, a blockade designed to destroy Britain’s economy by closing the entire European continent to British trade. The effect was the opposite of what Napoleon intended. Cut off from European markets, British manufacturers were forced to find new ones. They expanded into Latin America, the Ottoman Empire, and Asia. The Continental System did not destroy British trade; it globalised it. Meanwhile, the nations of continental Europe suffered from the loss of cheap British manufactured goods, and resentment of the blockade contributed to the coalitions that eventually defeated Napoleon (Zamoyski, 2018).

The October 2022 semiconductor controls are America’s Continental System. If they succeed in permanently crippling China’s chip industry, they will have achieved a strategic objective of historic significance. If they fail, if they merely accelerate China’s development of an independent semiconductor supply chain while alienating the neutral nations that resent being forced to choose, they will have handed China the one thing it could not have built on its own: the motivation and the political mandate to decouple completely.

The early evidence is mixed. Huawei’s Kirin 9000S chip suggests that Chinese firms are finding workarounds, albeit at lower performance levels. SMIC’s progress with multi-patterning techniques to achieve smaller nodes without EUV lithography is slower and more expensive than the ASML-enabled process, but it is progress nonetheless. Meanwhile, the Netherlands and Japan, under intense American diplomatic pressure, have imposed their own export controls on semiconductor equipment, but both nations’ industries are quietly furious at the lost revenue. ASML’s sales to China accounted for roughly 29 per cent of its total revenue in 2023 (ASML, 2024). The Dutch did not sever that circuit willingly. They were told to, and the resentment is real.

The deeper risk is strategic. Every nation that is forced to choose between American and Chinese technology will remember being forced. In the Cold War, the non-aligned movement, for all its incoherence, represented a genuine desire by newly independent nations to avoid being conscripted into someone else’s rivalry. India, Indonesia, Egypt, and Yugoslavia refused to choose between Washington and Moscow, and they resented the pressure to do so. The tech war is generating the same resentment among a new generation of nations that see themselves as customers, not vassals, and object to being told which equipment they may buy.

The Severed Circuit

The circuit, once severed, cannot be easily reconnected. This is the fundamental asymmetry of technological bifurcation. Building two parallel systems is expensive. Merging them again is almost impossible.

The Soviet Union discovered this when it collapsed. Decades of separate technical standards, separate manufacturing processes, and separate training systems meant that Soviet industry could not simply plug into the Western economy. The transition cost was measured not in billions but in millions of ruined lives, a halving of GDP, and a demographic catastrophe from which Russia has still not recovered. East Germany, despite the expenditure of over two trillion euros by the Federal Republic since reunification, still lags West Germany on virtually every economic metric. Technical divergence creates institutional divergence, which creates cultural divergence, which creates political divergence. The process is self-reinforcing and, beyond a certain point, irreversible.

For the nations caught in the middle, India, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the members of ASEAN, the choice of technology stack may prove to be the most consequential strategic decision of the twenty-first century. It is not a choice about which phone to buy or which social media platform to use. It is a choice about which technological civilisation to join: which standards to adopt, which supply chains to depend on, which data to share, which rules to follow, and which great power to trust with the infrastructure on which everything else depends.

India, characteristically, is attempting to maintain strategic autonomy, using American AI, Chinese telecommunications equipment, and Indian payment systems simultaneously. This is shrewd in the short term and may prove unsustainable in the long term, as the two stacks diverge technically and the pressure to choose intensifies. The Gulf states are hedging similarly, importing Western financial infrastructure while building Chinese-equipped smart cities. Africa, the youngest and fastest-growing continent, is the great prize: whichever stack becomes embedded in African infrastructure over the next decade will shape the technological trajectory of two billion people.

There is one more lesson from history that neither side will wish to hear. The great technology bifurcations of the past, Rome and Persia, Catholicism and Protestantism, the West and the Soviet Union, all ended not with a negotiated reunion but with the collapse of one side and the absorption of its remnants into the other. The reunification of Germany required the complete abandonment of the East German system. The end of the Cold War required the dissolution of the Soviet state itself. There is no precedent for two incompatible technological civilisations peacefully merging back into one. One system wins, and the other is dismantled.

The severed circuit is not a metaphor for a problem that might be solved by better diplomacy or a change of government in Washington or Beijing. It is a description of a structural reality that is already being built, factory by factory, standard by standard, satellite by satellite. The world is dividing into two technological civilisations. Both will function. Both will innovate. Both will serve the interests of the great power at their centre. But they will not be compatible, they will not be reunited, and the nations that choose wisely will prosper while those that choose badly, or fail to choose at all, will find that the choice has been made for them.